Manifesto for Making Space

Every morning, I sit in my chair next to the floor to ceiling window that

looks out onto the back garden. For a minute or so, I take in the flowers

and bushes, full with large green leaves that have burst forth after several

rainy days, and my eyes draw upwards, as always, towards the sky and the light.

I wiggle and get comfortable, legs uncrossed, feet flat on the floor,

hands resting one above the other with the thumbs touching (known in Zen as the

Cosmic Mudra). Then, I close my eyes and take three deep, slow breaths to

release the stress from my body and centre myself. In the fourth breath, my

attention shifts to my mind's eye, and I ‘speak’ two words

to myself. Make space. It is at this moment, the real practice of meditation

begins.

Throughout human evolution, making space has involved the literal expansion of

Life into the blackness beyond the exosphere, the outermost layer of

Earth's atmosphere. Scientists have theorised, made mathematical models,

and carried out thousands of experiments to define, describe, and understand the

Universe. And while it is possible for the human brain to intellectualise a

model relating the farthest reaches of this blackness to the tiniest space

between a single atom of hydrogen and its nucleus, there is in fact, nothing

that we can know with 100% certainty. Science is always based in measures of

probability. One story in the search for the meaning of life.

In meditation, my attempt to make space is like reversing the direction of a

spacecraft, which instead of racing to leave Earth's atmosphere through

temperatures of up to 1500 degrees Celcius, moves inwards into the realm within

my body, to investigate how I experience life through my senses, brain,

mind, desires, values and dreams.

After telling myself to make space, the immediate next thought that comes into

my mind is a question. Make space for what? I clear out clothes I do

not wear from my wardrobe in order to make space for more clothes. I give

away novels I will never read again to a charity so that I can make

space for more books. I throw away out of date food from the fridge

freezer to make space for more food. I tidy away materials and tools in

the studio to make space for painting more canvases. I even make space in

my brain for accumulating more knowledge. And so it goes on, ad

infinitum…

Yet, when I remove the ‘…for what?’, it is necessary to

move beyond the physical and open a whole other can of worms in a world where

the ever-present pressure for accumulating more stuff is felt at every turn,

and which cannot endure indefinitely. Because making space requires giving up

the modern global belief that a successful and meaningful life is an

ever-increasing Golden spiral of economic exchange and profit. In reality, it

is a quantum leap in thinking, to consciously make less, not more, of

everything.

Making space is growing less, but more nutritious, food. And also eating less (where rich countries redistribute the surplus to poorer countries, because there is plenty enough to feed everyone on the planet). It is giving up the delusion

that a diet pill will make me slim and healthy, while I have no discipline

to stop over-eating. It is understanding that eating less, in general,

counteracts the fat, cholesterol and calcium deposits that cause blockages and

inhibits the flow of blood through my arteries.

Making space is producing less humans on the planet. Because a global

population that keeps increasing, will at some point use up the available

resources and sway the precarious balance of all life on Earth. According to

one study in 2017, having one less child in a wealthy country can reduce a

family's carbon footprint by up to 58.6 tonnes per year over an

80-year lifespan*.

Suddenly, I am aware that my breathing has quickened, and my attention has

exploded into a profusion of intellectual distractions. And I have to

bring it back with effort, back to my body and the chair I am sitting on.

Making space is being aware of my breath. To be still for ten minutes each day

and intentionally slow my breathing to its natural rhythm of respiration,

inhaling oxygen and exhaling carbon-dioxide. I am making space in my

lungs and abdomen, and throughout the muscles and sinews of my limbs, right to

the extremities of my feet, toes, hands and fingers.

Making space is using my breath to push outwards from the solid, hard mountain

of a problem I cannot solve. Because when I enlarge the boundary, the

problem has room to breathe and move, and space to untangle itself and show me

a way through that I have not yet thought of.

Making space is to exercise and move my body. It is stretching on tip-toe, my

arms as high above my head as I can go, and breathing out to bend and

touch the ground as far as the spine will fold. Each vertebra and spinal disc

will thus stretch to make space, and counteract the compression exacted over

decades of wear and tear.

Making space is allowing my mind to rest. I do not say brain, because to

rest my brain would mean stopping its function to keep my heart beating and my

lungs breathing. A restful mind makes space between one thought and the next,

slowing down thought production, because in any one day day, I can only

act on a limited number of thoughts. And it is wiser, more useful, positive and

constructive to choose to act on thoughts that create joy and love and

connection and growing together.

Making space is staying with the discomfort of boredom, so that I can

listen and hear what I am telling myself about who I believe

I am, and what I think I am capable of.

Making space is sleeping peacefully, so that my dreams can resolve and

integrate the emotional onslaught of all that my senses battle through each

day.

Making space is writing in my journal all the words that run amok in my mind

that I do not need. Memories of past events, experiences and relationships

that persist and petrify into habits, which limit my growth and take away the

freedom to embrace uncharted waters.

Making space is appreciating all that I am in the present moment, for

through breathing, I embody the gift of life. And until I reach my

dying breath, breath is the fuel of life, the most valuable form of energy on

the planet.

* The climate mitigation gap: education and government

recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. By Seth Wynes and

Kimberly A Nicholas.

Rest weary traveller in the twilight mist of the glade

Pause upon the rings of a fallen tree as the daylight slowly fades

Unburden your back of the stick and bundle you carry with glee

For you cannot know its true weight while you are unable to set it free

I know you have carried it far, this bundle you treasure

Full of shiny objects gathered for good measure

Hard won trinkets I’m sure, yet lacking in substance

For they will tarnish with time and become a weightless existence

This stick, however, which has served you so well,

To ferry your riches after the mad rush to buy and sell.

It has been your companion through countless terrains of sludge

Your leaning post on days when tired limbs no longer budge

I will meet you in the glade, fellow traveller of the night

And ask how often you have used that stick, so deceptively light

To cane and beat into the pores of your skin

Such stories of guilt and shame inherited from your kin

Have you not suffered as one must, for duty and gain

The cruelty of vultures clawing deep into your pain

And I will say to you, nay, I will implore

Calm your beating heart and witness all that it endures

Breathe!

Breathe in the gentle sunlight that swirls and eddies from the East

Listen to the sound of the cool wind as it whispers through Nature’s feast

Sometimes quiet and melancholy, or rushing loud with a whoosh through the reeds

Feel the texture of its breath lifting away the veils of power and greed

Breathe!

Allow breath to seep and burrow into your flesh

To excavate the darkness and unbraid its solidified mesh

Give breath your tears, which have drowned in lakes and floods

In exchange for a kiss, an embrace, a cherished gaze from your beloved.

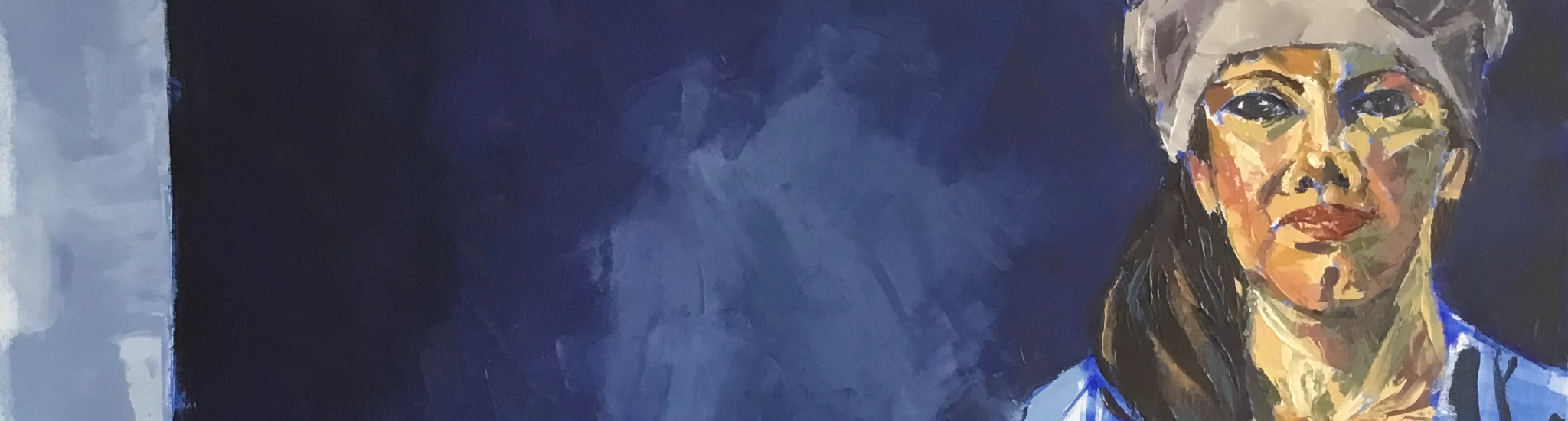

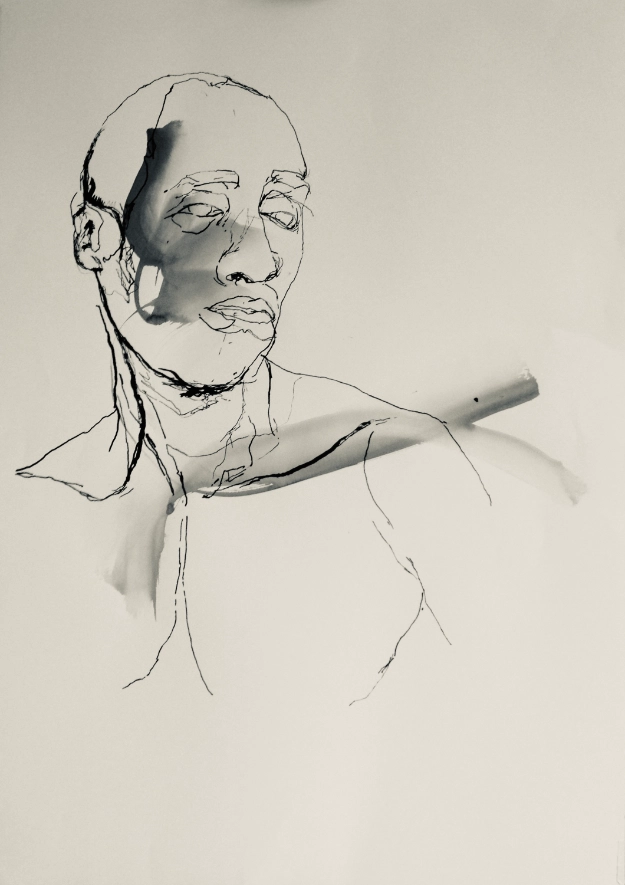

The first self portrait I painted was in sixth form college, aged eighteen.

A three-colour painting in blue, green and white of a sad and pensive young

woman seated on the floor, her head and unkempt long black curls laying at an

angle on one raised knee, looking into a mirror. At home, there was no study

desk, so large drawings and artwork had to be done on the dining room table or

on the floor. I did not paint another self portrait for almost thirty

years, until I joined a weekly art class in a small French village, when

I used photographs and found images to create a series of three self

portraits in oil, titled Fear, Guilt and Rage.

In the two years I studied figure and portrait at art school in London,

I’ve done several self portrait drawings and etchings, and I’ve noticed that

I do not like to look at myself in the mirror for long periods of time,

even after the initial discomfort of staring into my own eyes dissipates and

my attention is wholly focused on the drawing. I prefer to draw and paint

other people, attend to someone outside of my small, insular mind-world. To be

in a room with a life model, who is willing to keep still and be intently

observed for many hours feels an incredible privilege. I have an

abundance of time to measure and draw, mix paints and mediums, experiment with

composition, colour and scale, explore light and shadow, all in the search of

that elusive magic; to create a masterpiece.

My desire to tell stories underpins everything that drives my art. It has

always been there. In the first human tribes who told stories around a fire,

in my childhood obsession for Bollywood films, in the poems I wrote as a

teenager, and in the characters I created to inhabit and move through the

buildings I designed. Coaching is an extension of this desire in making

space for clients to express their own life stories.

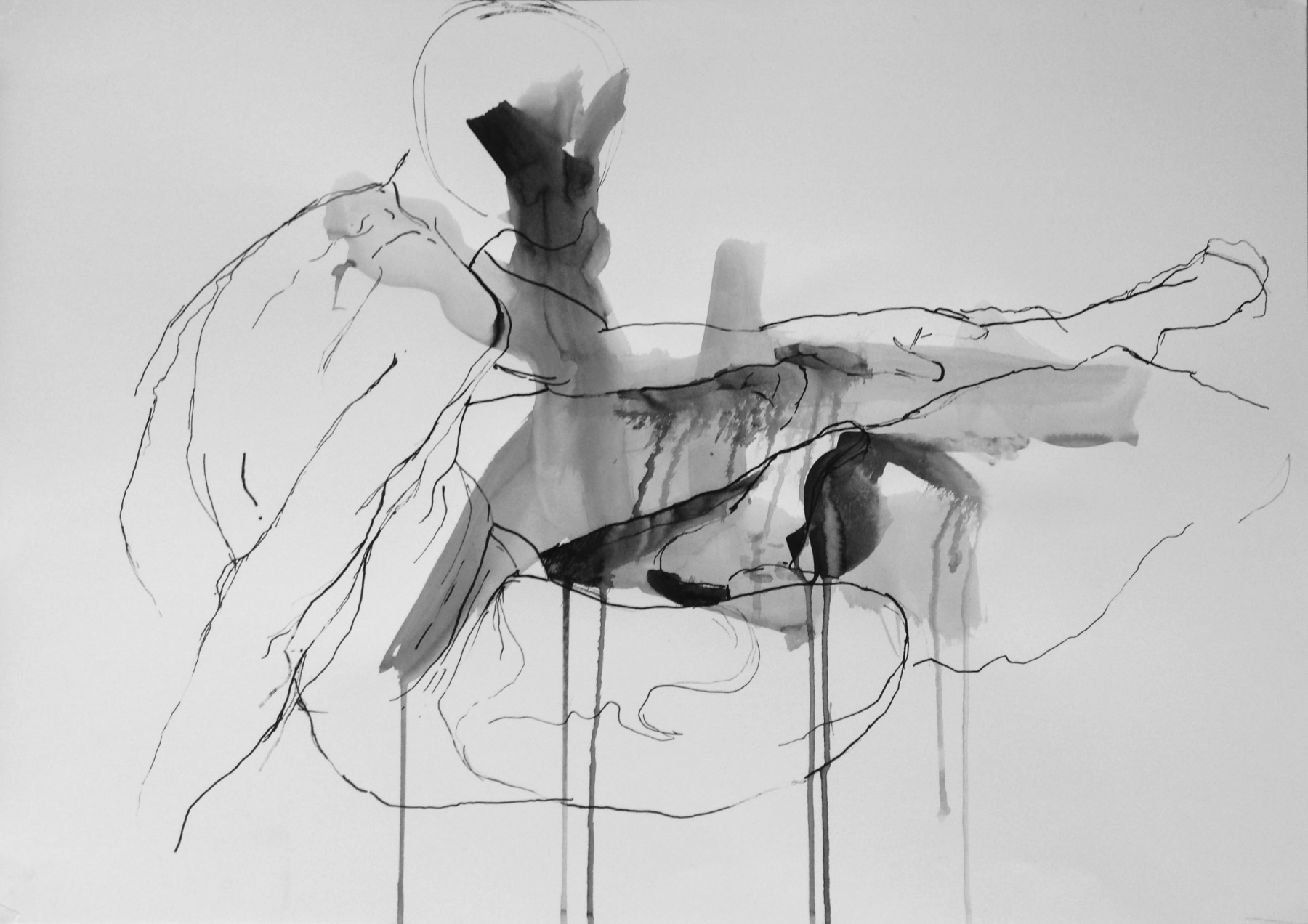

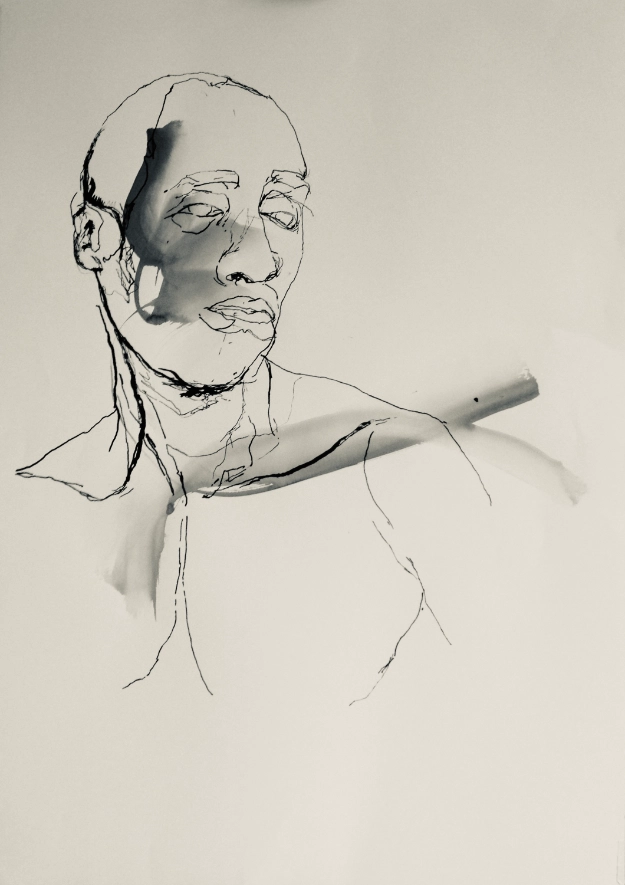

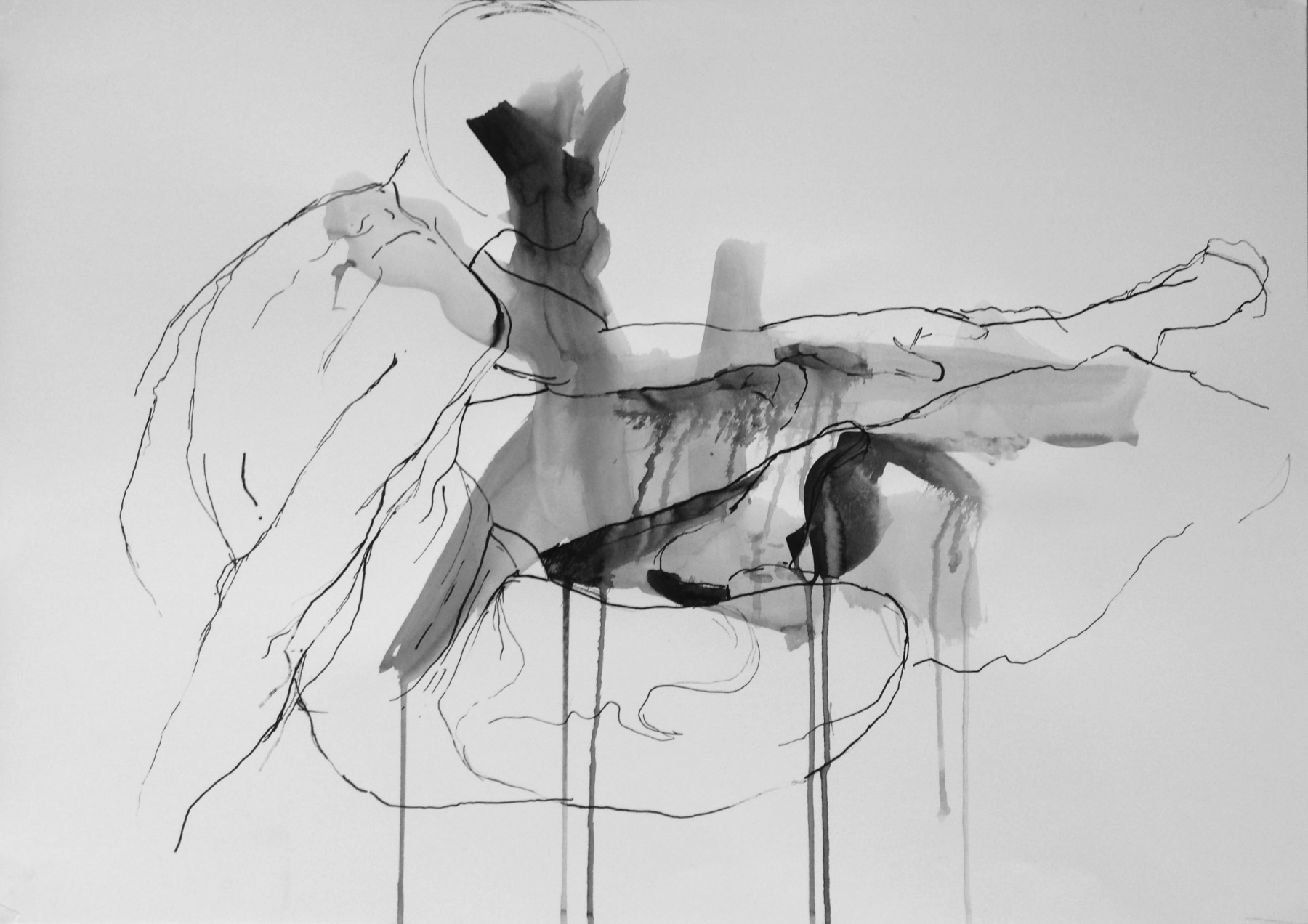

The human experiential realm is the pounding heart of all my creative endeavour,

and I believed that portraiture could be a direct thread into the web of

another human life. Bypassing the filter of words and language, I wanted

to render in paint memories of joy, happiness, love, and pain, elements of

history, family, and education. To paint the story of a life model that is

etched into the creases and wrinkles and folds of the flesh. That singular

alchemy of forces which combine to create a unique human individual.

Yet the more portraits I paint, I cannot help but think that

I am moving further and further away from the tale I intend to tell.

The model sits in a chair, sometimes with background hangings or with various

objects, fruit or flowers added to compose a context. As I observe and

draw and mix paints, I am wholly engaged in the task at hand; the neutral

stance of my body, the intuitive communication between my eyes and fingers that

move brush and paint within the parallel world of the canvas. I do not

notice that in her unnaturally still pose, my model has in fact become a still

life. And as I work to gauge how much blue, red, light, dark, shape, tone,

the stillness creates a distance between me and my model subject. For even

though I know that some artists converse with their models while they

paint, I am not able to attend to the alternate world of my canvas and

the human dimension simultaneously. There forms a crack in the ground between

me and she, a fissure delineating a vast distance, which thrusts my arrogance

into my own face. My finished painting may have a semblance of physical

likeness, but how dare I imagine that I could tell her story?

To observe and paint another’s face and skin and torso and limbs is to capture

nothing essential of who that individual really is. The niceties of small talk

does not even scratch the surface, because without the same sustained

attentiveness that I give to my painted world, I cannot know

anything of my model’s life story; where and how she was raised, whether she

has siblings, what her favourite subjects at school were, how she experienced

her first love, and loss, her previous jobs, and secret fears. In truth,

I know nothing of the story I had desired to tell.

In all the hours and days I have been painting, I have merely been

looking into a mirror, perceiving and interpreting my own story onto another’s

physicality. A kind of obfuscated self portrait, I suppose. It seems

impossible to truly paint her story when I cannot stand in two worlds at

the same time. For I cannot paint and communicate in our one sharedi

medium, words and language, at the same time. In conversation, it is necessary

to listen. Really listen. Which requires an engagement of all my senses to be

present to this living, breathing human, who is in constant motion.

She is not a still life. And neither is her story. Thus the dilemma of painting

a portrait goes on.

Meditation on Relationship

I step into the flat and the first thing I feel is the silence. Not

heavy or foreboding, just its presence; solid, encompassing nothingness.

I am back from holiday. My home is unfamiliar to me after two weeks,

which is enough time to shed the habitual repetitions of living and moving in

this space where I succumb to the daily habits of sleeping, waking,

eating, washing, painting, and occasionally smoking. This sudden sense of

discombobulation is unnerving. Home is the place where I am supposed to

feel comfortable in my skin, breathe with ease, sleep soundly. But I do

not feel at home.

My mind goes to the flat in Lyon where I have been cat-sitting for a

friend. I recall her saying how much she appreciates me taking care of

her cat. Really, it is Monsieur Mogg who has been taking care of me. Only when

he is not present in my environment do I notice the invisible threads of

relationship. The unfathomable sense of a companion creature who speaks

a language not of words, but of the eyes, a sharpening of the ears, a cocking

of the head, the pulse of breath undulating from his belly and through his

fur like sand dunes in the Sahara. In the heat of the summer, he lies on the

floor, his legs extended front and back to have as much of his body area as

possible touching the lowest, and therefore coolest, part of the flat. We

exist, the two of us, like Yin and Yang, walking around each other and passing

through rooms as though dancing a slow, heart-pounding tango. We do not touch

(Monsieur does not like to be constantly stroked) and in this unspoken

understanding, we give each other the freedom to be.

Back home in London, I lie in bed and find it unusually difficult to fall

asleep. I long for someone to be lying next to me holding my hand. Simply

this. For someone to say, it’s going to be okay, I’m here with you and we’ll

get through this together. The physical aching is just an expression of my

body’s need for emotional comfort. We call it love, sometimes. It is

compassion, empathy, acceptance, a witness to who I am. The greatest

privilege of being in relationship is getting out of my head and focusing on

the needs of someone or something else on a daily basis. To love another with

kindness. How wonderful to wake up and go to sleep with the sense of my

heart’s connection to another living being. To be utterly vulnerable and not

feel so alone in my little corner of the world. This is what Monsieur and

I ddid for two weeks. Take care of each other and be witness to each

other’s life.

It occurs to me that so many of my relationships with people have been fraught

with tension. One-upmanship, competition, measures of worthiness, flirtation,

manipulation, sexual prowess, standards of beauty, expectations, and so on.

The list is endless because the reasons and justifications for “power over”

in any relationship are endless.

On holiday in Lyon, I spent some wonderful days with my ex-husband, Denis.

My friends regularly ask whether we will get back together again, but this is

an erroneous question. On this visit, I realise the real power of

relationship lies in the willingness to clear away memories of the past, both

good and bad. I used to be terrified of forgetting the incredible years

we had together. In hindsight, I see that the mind mostly holds onto the

bad experiences (our defensive animal nature), solidifying the reasons for why

I was right and he was wrong during the time of our separation. The

seismic leap to “forgive and forget” means we can both love each other for who

we are in the present, creating a new relationship which often feels more

profound than the previous one.

Every relationship has a beginning and an end. Nothing that lives and breathes

lasts forever. So I hone in on the present. The Now. And in the now, my

objective reality is that I live on my own. However, I am not alone.

I sit in the garden and watch the plants gently swaying. I listen to

the wind rustle through the trees as I quietly smoke a cigarette (the

paradox that I may be killing myself is not lost on me). I feel

Nature breathing as I am breathing. I have no idea what will unfold

tomorrow, no matter how many narratives my imagination lets loose in my mind.

I feel the longing, the sting of water in my eyes, the tears as they roll

down my cheeks. And to feel these vibrations and rhythms of life, as vast as

the sky and oceans that take a unique form, moment to moment, day to day,

season to season, is something to be grateful for. Because even though

I may wish to dance with joy and happiness and love and fulfilment all of

the time, what a relief it is to also know that sadness, fear, grief and anger

are not constant. Every feeling and emotion expressed will pass in time, and

remembering this, I see all emotions are equal.

And what kind of relationship will I choose? I have made my mind up

not to resist the ebb and flow. To accept with grace my body, feelings,

emotions, thoughts, dreams, stories, longings, and all experiences. One day,

all of it will pass.

15 March 2020. It is the first day of an emergency two-week lockdown in Spain (which would be extended to a

total of 8 weeks). We are to stay in our homes and only go out for food supplies or medicines. It is an

unprecedented and highly conflictual imposition on people's civil liberties, but the only way to

counteract the infectious disease claiming lives by the thousands on a daily basis. Though it feels shameful

to admit, my immediate reaction is a huge sigh of relief. Not because I am doing my part to protect

myself and my community, but because I suddenly feel released from the burden of having to meet people,

make friends, learn a new language, increase my knowledge of local culture and history, and all the other

demands of moving to a foreign country.

While many people were horrified at the prospect of isolation or being on their own for such a length of time

(which in hindsight had both positive and negative consequences), the pandemic gave me the gift of solitude.

It was my chance to reclaim a sacred space, where there was no one to judge me, control me, or pressure me,

neither externally nor by self-imposition.

I made it my mission to dance for an hour every morning, eat healthily and write. I wrote every day,

including the weekends, because time had lost its rhythm. No one was going out to work and no one was relying

on me for anything. I was a lone spirit swimming in the midst of a global catastrophe, somehow oddly at

peace with the reality of my mortality. I worked with discipline and even felt reluctant to have video

calls with friends and family whom I perceived as invading my solitude. It was a precious and creative

cocoon, which had been a dream for many years, though I'd not imagined it in such dire circumstances.

I used to believe that solitude was a self-indulgent luxury; wasted time and energy in the art of navel-gazing,

which does very little for the greater good of societal productivity. Since childhood, I believed my

wanting to be by myself was wrong. I had to trick my grandparents and aunts (with whom I lived) into

thinking that solitude was really for the purpose of doing my homework or studying for a test at school.

I had to pretend that having time for myself was not my preference, but a drudgery for my education, a

reason that resonated with the goal to somehow better myself. To have solitude just for being who I was

was not the purpose for which I was born, because my waking hours were meant for collective female

rituals such as cooking, cleaning, washing, making crafty things for the house and beautifying myself. That

I should want to read books, or write, or dance, by myself, for my own enjoyment. God forbid! Such

intellectual pursuits were not meant for girls who would grow up to be good and decent Hindu women.

Yet when I got divorced some years ago, solitude became a necessity, a sanctuary of time to grieve.

I remember a similar feeling when I came to London at six years old to live with my family in a

council flat in Finchley. My three sisters and I shared a bedroom, sleeping top-to-toe, two of us in each

bunk bed. An entire bedroom for one child was unheard of in the context and time my parents lived in. There

was a damp spare bedroom where none of us could sleep and nothing was ever done to get it fixed. My mother

used it as a prayer room, for there always had to be an altar for the gods and the dead, who did not live on

this earthly plane. In that crowded flat, I felt suffocated living with a family I barely knew, and

hated returning from school to a home where my sisters bullied and fought and swore relentlessly. To be with

them meant facing the constant threat of anger and violence, which multiplied threefold when my mother got

home from work.

So what does a child do in this situation? I retreated into my mind — into books and stories and studying.

I think I made an unconscious decision to prefer everything that was different from my sisters so

I didn't have to belong to the family collective; solitude gave me strength and made me resilient.

After my marriage ended, however, solitude was a conscious choice. It was the most difficult experience of my

life, when the woman I'd believed myself to have evolved into over a lifetime, fell apart in a way

I could never have predicted. The only thing I knew to do was to submit wholeheartedly to my

creativity. Through dancing and writing, I reclaimed a sense of who I am that no other person is

able to see or fully comprehend, the deep part of me that is the seat of confidence, courage, self-belief and

enduring patience, which cannot be shaken by external events or people.

During lockdown in Spain, solitude was a period of time to live with questions and doubts about the past and

future. It was an experience I imagine like the myth of the fire phoenix, when old identity dies and

burns, and the phoenix is then reborn with a clean slate of innocence to create a new life. Even now that

I am back in London, as the pre-pandemic ‘crazy, busy’ returns with a vengeance, I am determined to

hold this solitude at the centre of my core. To make time and space to be still, on my terms alone. In

lockdown, I completed my novel, and despite much encouragement from friends and family, I have

decided not to publish it. Because to say NO in a society that is obsessed with global self-promotion of all

that was once sacred is my choice and my responsibility.

It is February in London. The bone-chilling force of the wind seeps stealthily

between the woollen layers of my coat, scarf and gloves, then jacket, jumper

and vest. My muscles are braced tense against the cold, my arms and hands

wrapped tight around my torso, as though I could squeeze myself to the

point where my skin would become impermeable to the freezing temperature

outside. Strangely, this is also how I sleep at night, arms wound around

my chest. When my eyes are closed, the only world I can see is within,

inside my mind and breath. With my arms I am trying to contain the vast

and howling emptiness within, craving in the darkness for numb unconsciousness.

This concave curled-up-like-a-caterpillar position of the body is often

associated with a sense of protection, when the spine curves to shield softer

internal organs; seeking safety, comfort, or a rallying stance to shut out the

external world. Like every human being, I began the adventure of life in

this foetal position within my mother's womb, where my skin was vital for

receiving nourishment from the environment. I imagine my mother nourished

her own connection to me, the child growing within her body, by regularly

touching and feeling the skin of her stomach.

Touch is the primary experience of love. When a father cradles his new born

baby, when a mother gives milk from her breast, when a parent is willing to

wash and clean their toddler and gently rock her to sleep, they are giving

love. Sadly, by the time I became a child and was finally able to

coordinate my limbs enough to reciprocate my parents' love, my father was

no longer alive and my mother was exhausted with the grief of having lost him.

I don’t know exactly when the shift occurred. Perhaps it was a gradual

acceptance of breathing into my lungs the stifling air of religion and the

eternal shame of being born a girl, but we became a family who did not do

hugging. My mother was a single parent with a full time job and raising four

children. Skin to skin was a rushed affair; soaping and scrubbing in the bath,

yanking knots and plaiting hair, or slapping in admonishment for misbehaving

and fighting with my sisters.

Children do not necessarily understand their craving of love through touch,

but they are highly adaptable. I thought I could win my mother's

love with my smart brain. I studied hard and achieved top grades in my

class throughout junior school and secondary school. Following my

A Levels, I decided to study Architecture because it integrated my

skill in maths and my love of art and design. I assumed my mother would

be proud that I was the first of her daughters to go to university. Until

I noticed part way through my studies that her expectations had changed.

Sure, she didn't mind that I studied for a while in order to get a

decent job, but when she found out it would take 7 years, she was

exasperated. “When will you stop this studying lark and get married and

settle down? Start living a real life?”

What a disappointment I was. My years of effort had not measured up. So

I did the only thing I knew to do. I searched for love's

touch elsewhere and ran into the arms of the first man who gave me a gold

bracelet (for gold is the preeminent symbol of love for Indians). By then

however, I hated my fat body and lumpy skin, and had no idea what it was

to feel loved by touch. Losing my virginity (which must be the most horrid

expression invented for first physical love) gave me no joy, because I did

not love myself and had no confidence in my own worth. So I could not see

what any man would find loveable about me.

Yet I carried on searching. And although I see it only in hindsight,

I embarked on numerous, and ultimately disastrous, relationships because

I was desperate to be touched. My skin constantly longed to feel that

essential experience of love. I wanted to be loved by someone special,

who I knew was waiting out there just for me. I believed in the

delusion of ‘The One’, who would always keep me safe, take care of

me, and with whom my body and skin would grow old.

The realisation was a long time coming. That education and culture is wrong.

The dating sites, relationship books, women's magazines, parental advice,

all misguided. Because we make the mistake of believing that love comes to us

from ‘out there’ and that we have to be ‘good’ people

to deserve it. We spend our entire lives in search of love from others,

imagining that we need to behave in a certain way or agree to certain

conditions in order to receive love's touch. But stop for a moment and

look. Our skin, the largest living, breathing sense organ of our body, is

permeable both ways. It can absorb touch from the inside out, as well as from

the outside in. We are already, and have always been, touched by love, which

is within us and in our ability to create and feel in abundance, for ourselves

and for everyone else.

And because we are biological, organic, living beings, one day we will die.

There are no ifs or buts about this truth. While we are here, however, the

relationship we have with our Self is ever-present. And just as our skin and

body is continually transforming, so is the potential to love who we are

unconditionally.

The next time you feel like curling up like a caterpillar in isolation, go

beyond the defence mechanisms. It is a simple change in direction to go within

and be vulnerable to accepting and loving yourself in the moment. No matter

how vast the chasm of emptiness feels, love is not about filling it with

heart-shaped cushions, jewellery, chocolates, or expectations. Give the love

within your skin space to unfurl its wings and fly.

Please, subscribe to the newsletter here!